Exploring The Brain: Synaptic Pruning

Researching the intersection of Neural Efficiency, Popcorn Brain, & Signal v Noise

Introduction

After an in-depth exploration on discipline, I thought I’d go even deeper.

From a high level, there were many contradictions innate to upholding discipline, some of which we can control and other parts less so.

A thread throughout that exploration was that discipline involves a lot more nuance than the common narrative we are lured into.

However, awareness of its flexibility is more than just a mindset shift; it includes a rewiring in our approach to adopting challenging goals.

Ultimately, your brain adapts to whatever you feed it, which led me to the topic of synaptic pruning.

How do you work with its processes when you’re not in control of them?

That is the question we are going to answer, through a topic that has long been on my list.

You may not have heard of pruning, but it plays a major role in our day-to-day actions and decision-making.

Alongside that, it has a life cycle of its own.

What is Synaptic Pruning?

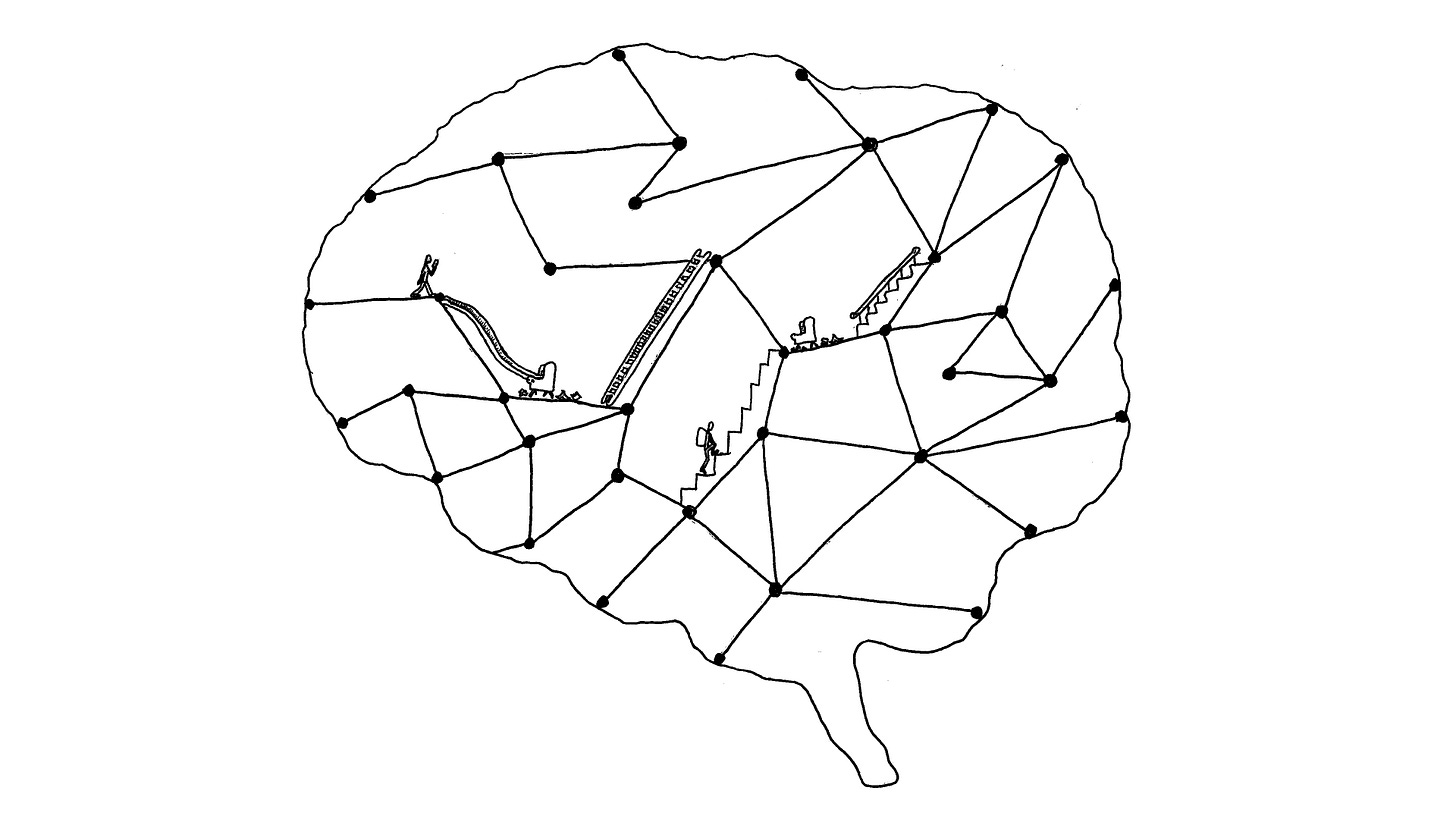

Synaptic pruning is a natural developmental process in which the brain eliminates unused or weaker neural connections to strengthen ones that are used more often.1

Its process is a constant throughout our lives but happens more intensely in early childhood.

For some context, synapses are the connectors between neurons, and through pruning, the ones you use frequently are reinforced - hence the name synaptic pruning.

That is the science behind the phrase “use it or lose it”.

It takes place in advanced reasoning, such as language, problem-solving, etc. and already you may be able to identify the importance of our experiences in this process.

From two to four years old, the synapses peak at double the average adult brain, then levels off slowly until a steep drop during adolescence.2

Essentially, by having a range of experiences from young, your networks are less restricted in catering for your immediate demands, and instead allow you to nurture those required of you in the future.

It links to a point from episode two of my podcast reflections, where I highlighted how experience in a range of activities provides a better foundation to later hone in on.

Like transferrable skills, the learning patterns that are created in those crucial developmental years thrive on that period where learning, rewiring, and adapting feels more natural.

It doesn’t mean you’re too late though.

You can still learn something new, and you may even be in a better position to adapt.

However, from a physiological perspective, it will take more effort to pivot.

Overcoming that inertia isn’t just wishful thinking and me blindly saying “you can do it!”

A very recent study by Cambridge’s Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit explored the pace of pruning and cognitive capacity throughout our lives.3

It highlighted that the brain’s communication networks become increasingly refined as we enter our early thirties.

“Communication networks” encompasses the structure of the brain but focuses more on its function, where the study found “adolescent-like changes” in the wiring of the brain up until the early thirties.

From my perspective, this fact gives an even bigger nudge to be disciplined in the areas that matter to you.

We are aware of the mental side of discipline, but the physiological side is probably more important and not talked about enough.

For example, the pressure to have everything right first time can be what blocks your blessings in the long-term.

Even if you find yourself committed to something for what you feel is a phase of your life, the result is a more focused, intentional, and aligned version of yourself that will approach the next thing with more appreciation for what’s to come.

This comes back to the point that pruning makes the brain more efficient, so being self-aware of how your energy is fuelling it can be influential in the pursuit of your disciplined self.

The Popcorn Brain

The term ‘popcorn brain’ was first coined in 2011 by researcher David Levy.

He described this as: “the mind being so hooked on electronic multitasking that the slower-paced life offline holds no interest.”4

My first interpretation of this was us being fiends for our phones, which is not glamorous to say… but sometimes its true.

The impulse to turn to our phone is often to fill a gap of time which now feels uncomfortable or bizarre without our phone present.

If you check your screen time, it tells part of the story when it comes to popcorn brain.

Unless you’re using your phone for work, that screen time is a cumulative representation of the times you chose to avoid boredom; the moments where your brain should’ve had some respite.

We are not perfect and cannot be focused 100% of the time, but I think it’s a good overview to have.

However, it would be an underdeveloped exploration if I only looked at phones, as the “multitasking” element can also persist when we have multiple screens in front of us.

Although phones do play a big part, there is a bigger picture.

On average, we spend 42% of our waking hours looking at a screen.5

The eye care industry must be grinning ear to ear…

It genuinely shocked me, because some of that will be on a laptop, TV, phone, but what proportion of that do you think is spent consuming rather than creating?

When aggregating the content you consume, you can become anxious and misaligned when unable to channel the information we process.

Now you’re stressed and frustrated about feeling stressed and frustrated.

So the value of intention here is clear.

Curate that mental diet through your for-you-page, leave the phone out of reach when you don’t need it, have more conversations, and we could go on.

On the conversation of pruning, I raise popcorn brain because it is a nice foil for constant digital stimulation which will impact the wiring of your brain.

‘Popcorn brain’ is nothing more than a metaphor that allows you to visualise the impact of this stimulation.

As highlighted prior, synaptic pruning strengthens what you repeatedly use; we don’t want to crash and burn as we teach our brain to reinforce pathways for low-value inputs while weakening the circuits for sustained focus.

The University of California, who have been studying attention spans for over 20 years, found that in 2003, people’s attention averaged 2.5 mins on any screen before switching.

From 2018, it averaged 47 seconds.6

You’ve heard of falling attention spans, but having numbers there definitely makes it more apparent.

Nonetheless, it’s not all doom and gloom because the impacts can be reversible when you’re not too deep into that self-reinforcing loop, which I doubt you are if you’re reading this – hopefully I’m not wrong.

To bring some light to this situation, you are on the side of undoing the impacts of having a popcorn brain; seeking windows of lower stimulation and restoring your sensitivity to slower-paced environments.

This is at the heart of selective ignorance, as you are trading noise for signal.

The more free time you can allocate to creating or being away from technology, the more that boredom and silence feels grounding, which is key in maintaining agency over the pace at which you make decisions and travel through life.

Signal v Noise

“Signal refers to the meaningful and desired information being transmitted, noise represents any unwanted or irrelevant disturbances that can interfere with the signal.”7

Noise and signal are relatively subjective counterweights.

In a business sense, you may hear of Steve Jobs or Elon Musk treating business priorities as the signal and everything else as noise.

Their obsessive inclination to follow the signal has led to breakthroughs in our lifetime that will be spoken of for many years to come.

However, a commonality in their perception of ‘noise’ is in the abrasive approach to building relationships.

Whether it’s the stories of Jobs being extremely demanding and stubborn in the workplace or Elon’s personal relationships, the feelings of others naturally go on the backburner.

Some will say, it is a great sacrifice to live so precariously, others will disregard it.

Either way, this bursts the bubble of maintaining the position of being a frontrunner in an industry that requires your all.

I preface this section with the extreme example of signal versus noise because the empowerment from ‘self-care’, ‘self-help’ or ‘self-improvement’ pertains to managing your balance between these two forces.

Each resource pushes you to recognise this.

Prior to looking outwards, we must ask ourselves and be honest in whether we are prioritising the right things.

That looks like prioritising what has the biggest impact, rather than doing what is easiest at the moment, which is much harder said than done.

These private choices determine how you show up publicly.

In a similar vein, we can see this in Jobs and Elon’s approach to actualising a vision as best as possible.

There is a persistent ruthlessness that produced visible success, but may have damaged what success looked like in their personal lives.

The mirror being shone to ourselves is how ruthless we are when taking action on things that matter to us.

Are we backing our declarations with actions or sleepwalking and almost weaponizing something that sounds nice to avoid something deeper?

Either way, the central assertion is the unbiased nature of our brains and what we feed it. Each time you choose distraction, you teach your brain to choose interference over the signal.

Back to pruning, this effectively rounds of the discussion we’ve had throughout this post.

One thing within our locus of control to take away is that:

To reinforce a certain way of thinking is becoming hardwired to seek situations that agree with it.

As with many things, we have to find the inspiration, light, and nuance within ourselves before we share it with the world, in which pruning is a process that cannot be rushed.

Throughout this post, I’ve learnt that there is real truth behind acting like the person you wish to become.

I would like to hear what you’ve learnt from looking deeper into our physiology: Has pruning changed the way you see yourself?

The link between synaptic pruning and “phases” of commitment really landed. Even if something doesn’t last forever, it still shapes who we become next. That took a lot of pressure off needing to get everything right the first time.