Unlearning the Invisible Rules of Stress: Does it make or break you?

Stress is a personal journey and fundamental to understanding ourselves - It's time to swap out assumptions for research as we uncover what it means for you.

Abstract

On a ‘bad day’ the smallest thing can irritate us, tipping us over the edge.

We know stress is inevitable, but is there a way to strike the perfect balance?

Like Jenga, one wobble of the blocks keeps it enticing and invites us to test the waters.

It’s impressive when everything is in place, calculated moves have been made, and you seem to have everything under control, but when the structure falls, reality strikes and we are forced to look within.

Resilience was tested and each block was a challenge, but there was only going to be one end result.

After exploring what passion means to me, I noted that incorporating it within our lives takes effort and at some times is arguably ‘stressful’ to keep up with.

Not only this, but The Spotlight Effect also presents a psychological element to life’s challenges.

Our daily lives have the capability to hold us captive in the fight or flight response through chronic stressors - those unrelenting challenges we face every day.

Acute stressors are sudden, short-term challenges that can unravel the coping blanket put over our chronic stressors.

In this post driven by research, we will explore an array of topics under the umbrella of stress and devise actionable tips to be taken away for yourself today.

Research & Discussion

“You’ll understand one day.”

Their experiences afforded them an inner joke and sometimes with a chuckle, those were the words my parents would use to put things into perspective.

There’s not much I could say to be honest.

In the face of unrelenting challenges, where the stakes couldn’t be higher if they tried, I knew that they had been through experiences I would never have to go through because of the toil they endured in order to give me a better life.

As stress is very much a physiological response as well as a psychological one, seeing someone being anxious, irritable, or worried implied being ‘stressed’ as I was growing up.

It wasn’t a word you would ever ask the meaning of - you would only assume.

I would avoid using the S-word because it never felt right to problematise my situations, and at times of heightened emotion, my parents’ words broke the self-fulfilling prophecy of being ‘stressed’.

I never used the word, but I thought I knew what it meant.

Before conducting any research, my understanding of stress was it being a reaction or response, not a prolonged state of being.

In a lot of cases, our baseline mood, physical state, and nutrition can cause us to lead unhealthy lives, to which when we tell ourselves we are ‘stressed’ we perpetuate that stress response.

Among a variety of entry points into the topic, my motive to explore stress is to develop an understanding on how experiences differ across different ages and to learn of the facts that provide reason into these experiences.

Where do I start?

Typically I would start with a definition when exploring a subject deeply, but this one is different.

My first port of call was to watch an award-winning documentary on YouTube to develop an overview and hopefully an angle to approach the topic of stress.

It did get quite technical at points, but I extracted four takeaways from it:

A stressed body contributes to the ‘fight or flight’ response, which activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The SNS can compromise the parasympathetic nervous system which affects digestion and basic bodily functions

Stress doesn’t cause problems; it is a response that aggravates our reaction

The way we frame our experiences can condition us to react in a certain way; what you don’t express in life you’ll repress until it expresses itself as a disease or dysfunction

Time doesn’t heal all: The amygdala is a part of the brain where emotions are processed without a clear perception of time, and therefore emotional/traumatic memories can feel as vivid as when they first occurred, even years later

I realised that there isn’t enough awareness on what exactly stress is, and despite it being a developing subject area, even a base understanding from school would be helpful in understanding ourselves better.

Stress is very much a personal agenda and the purpose of this post is to relate the research to our experiences.

When looking at websites that talk about stress (made for the general public), they do not make the effort to dispel the fact that stress is not only a mental response.

The information they present can be misconstrued as it being a mental condition that then affects the body as a consequence:

NHS: “Stress is the body's reaction to feeling threatened or under pressure.”

World Health Organisation (WHO): “a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation.”

Also WHO (in PDF): ““Stress” means feeling troubled or threatened by life.”

In my opinion, a definition can be subjective and clear, but instead there is clear divide in what exactly stress really is.

Unless going into scientific or detailed research, understanding what stress is can be challenging, and for that reason I took upon myself to look into the science behind it.

The Stress Response

When looking into the history of stress, there was a name whose work was commonly cited as a basis for research today.

Hans Selye’s work was focused on the field of medicine and is considered to be one of the pioneers of modern stress theory.

However, it is easy to be misled and it is convenient to credit the word ‘stress’ to Selye as if he invented the word.

There were an overwhelming amount of articles which pointed towards this, draping a red carpet to attribute his legacy to his subject area despite the word ‘stress’ originating from the field of physics as a way to describe strain on a physical body.

In a 2005 research paper looking at stress and health, they describe Selye’s use of ‘stress’ to represent the effects of anything that threatened homeostasis, which is the body’s natural ability to maintain a stable and balanced internal environment.

It is highlighted that the stress response is an adaptive process, in which the actual or perceived threat is referred to as the ‘stressor’ and the response to the stressor is the stress response.

Despite the stress response being adaptive, a general consensus was that our bodies were not designed to be constantly activated.

We call this constant activation ‘chronic stress’, whereas moments that invoke a short-term reaction come under the umbrella of ‘acute stress’.

The paper describes what happens internally when we get/are stressed:

“Stress hormones are released to make energy stores available for the body’s immediate use. Second, a new pattern of energy distribution emerges. Energy is diverted to the tissues that become more active during stress, primarily the skeletal muscles and the brain… Less critical activities are suspended, such as digestion and the production of growth and gonadal hormones.”

What immediately caught my eye was the abandonment of basic bodily functions as it mirrored what I had listened to in the documentary.

As chronic stress is a response over a prolonged period of time, it perpetually shuts down these functions, weakening our immune system and causing us to be more vulnerable to diseases.

If we were to look into Selye’s 3-stage theory called the General Adaptation Syndrome, this supports the consequences mentioned above on how stress can impact us in the long-term:

Stage 1 is the ‘Alarm Reaction’. This the body’s innate reaction to a stressor and is where the ‘fight or flight’ response takes place. The energy diversion to our skeletal muscles and brain described earlier essentially puts us in ‘survival mode’.

Stage 2 is ‘Resistance’. If the alarm reaction continues, your body adapts to the situation in an attempt to return to homeostasis. Selye found that this stage occurred in the rats typically 48 hours following the stressful event, where we experience higher blood pressure and higher glucose levels in the blood.

Stage 3 is Exhaustion. The body has depleted its resources and should the stress continue, exhaustion becomes apparent.

When looking at this theory, it is clear to see that it is very much an adaptive response only suitable for the short-term. In part, it primes us for survival whilst being an unsustainable way to cope with stress.

The constant activation that many face is ‘chronic stress’ which causes fatigue, being prone to illness, and consistently low energy.

These are examples of symptoms of the wear and tear on our bodies and our stress response system, where the Centre For Studies on Human Stress (CSHS) details the different types of chronic stress.

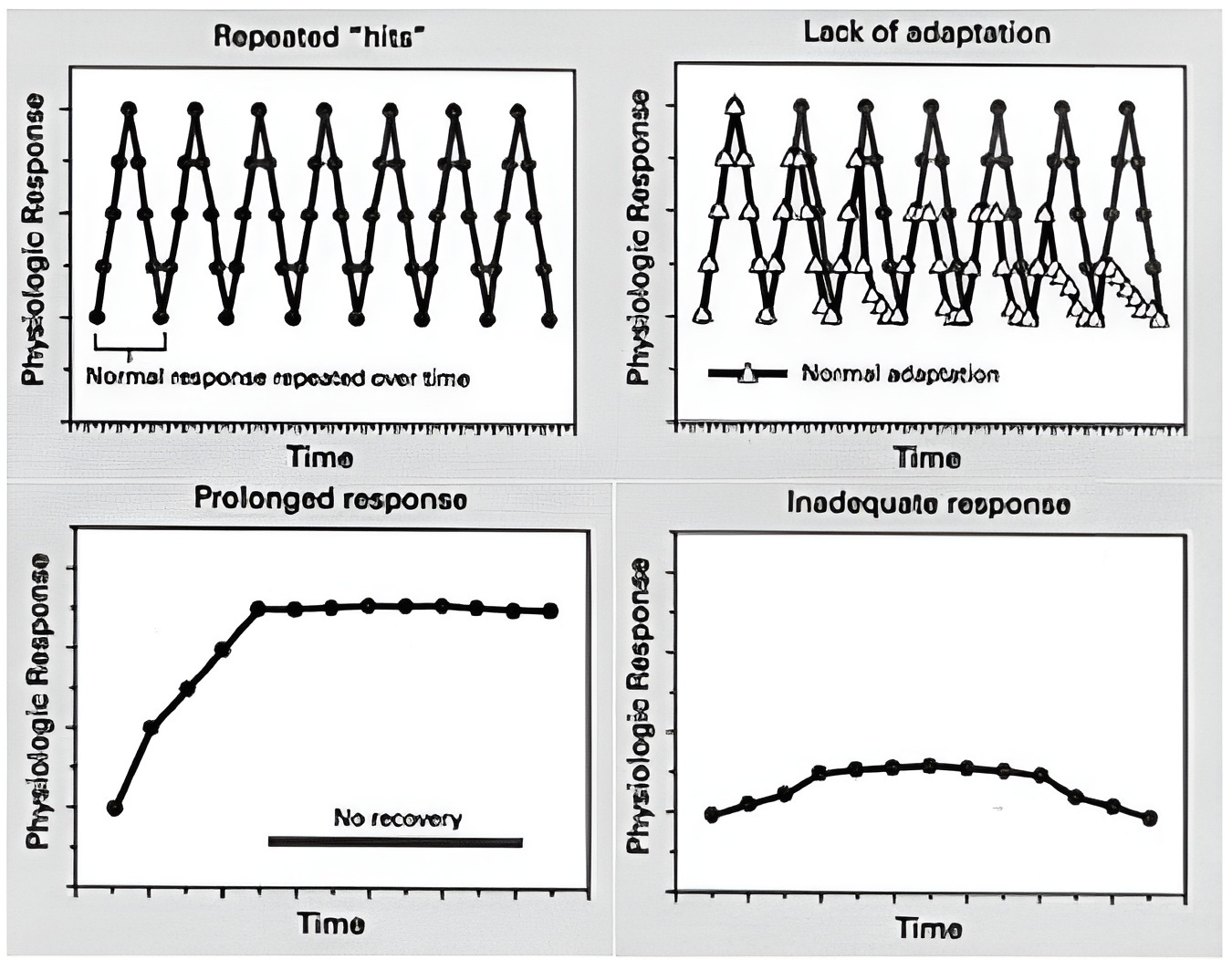

The visuals for each type of chronic stress response are as follows:

Repeated “hits”: If we have repeated activation of the stress response over long periods of time, then there is wear and tear on the stress response system. It was not designed to be constantly in use like this.

Lack of Adaptation: Normally, if we are exposed to the same stressors, our system can get used to them and we don’t respond as much. This is called habituation. The wear and tear of chronic stress can lead to an inability to habituate to stressors.

Prolonged Response: The wear and tear of chronic stress can result in stress hormones levels failing to go back to normal after stress. When this happens our other body systems also stay in high alert (e.g. blood pressure, blood sugar).

Inadequate Response: In some individuals, the wear and tear of chronic stress can result in an inability to respond normally to stress in the future. The body’s stress response system simply goes on strike or burns out and we don’t have enough stress hormones around.

The HPA Axis & Stress Hormones

This is where we get a bit scientifical.

In terms of terminology, we’ll walk through the body’s internal reaction in more depth using the information we discussed prior.

There was a specific phrase that kept appearing over and over again called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, also known as the HPA axis.

It plays a crucial part in understanding stress as it refers to our stress response system.

To summarise where the name comes from, the hypothalamus sends a chemical message to the pituitary gland, which then leads to another chemical message from our brain to the adrenal glands that reside on the top of our kidneys.

This message says ‘secrete cortisol’.

Cortisol is what we call a steroid hormone, and is essential for many normal or basal (resting) bodily functions.

We have a steady stream of the hormone in our blood as it regulates metabolism, immune response, and energy levels, allowing us to maintain an internal balance.

Too much of it and we may face anxiety, memory issues, weight gain, and high blood pressure.

Too little of it and we may face fatigue, depression, weight loss, and low blood pressure.

I made the link between this and the findings in the research paper titled: ‘Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition’ Lupien et al. (2009).

The researchers stated that periods of heightened stress often precede the first episodes of disorders such as depression and anxiety, raising the possibility that heightened HPA reactivity during adolescence increases sensitivity to the onset of stress-related mental disorders.

The effects of stress in adolescence is a topic that will be explored further, premised on the common notion of ‘hard life now, easy life later’.

As highlighted by the diagram and explanation for the inadequate stress response earlier (No.4), I couldn’t help but draw parallels between the narrative of the paper, cortisol, and our ability to manage stress.

The wear and tear discussed prior is often referred to as allostatic load, which can decrease a person’s ability to respond to stress effectively. Over time, repeated activation of the stress response system (especially cortisol and adrenaline release) can dysregulate the body’s normal response to stress.

As a result, some may become overreactive to mild stress leading to anxiety and irritability, whereas others are desensitised to stress leading to low motivation and emotional numbness.

In addition, the dysregulation of cortisol can amplify these symptoms.

This reaffirms the importance of managing stress for our future self, as the impact of the daily stressors we face can be reversible, however stress-related conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and neurodegeneration (the damage of our nervous system) have long-lasting and in some cases permanent effects.

Even as a young adult, the risks of prolonged stress cannot be ignored.

Childhood stress has been associated with higher risk of dementia, specifically Alzheimer's disease (Donley et al., 2018).

It is generally thought that the developing brain can withstand high levels of stress due to the neuroplasticity of the brain, but as we will explore further, this is not always the case.

Adolescence: Stress & Aging

“Not all stress is bad; in small amounts with the proper support, experiencing stress is a necessary part of healthy development.” (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2014))

Does stress at a young age make us more resilient?

Multiple studies point towards mild to moderate stress during developmental periods promoting an adaptive response to adverse situations later in life, boosting stress resilience.

A widely held belief is that facing challenges when younger forges you to become more resilient, but the relation between stress and resilience is poorly understood in the scientific world with many experiments on a small scale leading to inconclusive results.

Exemplified by the following quote, it is clear that there is still a long way to go.

“Stress during development is generally thought to evoke negative behavioral effects later in life … However, prior studies also support the ability of adolescent stress to confer stress resilience in adulthood, using a number of stress models… The impact of adolescent stress differs that of stress imposition earlier in life, where the data generally report detrimental effects of stress.”

So, are the benefits of enduring stress from young just conventional wisdom?

When reading on the interplay between stress and resilience in adolescence, I came across a 2022 article that pointed out that adolescence is a period of “immense opportunity” due to the heightened plasticity of the developing brain.

They then went on to talk about “controllable stress” and “uncontrollable stress” to they suggested that in adults, the experience of controllable stress may buffer an individual against the negative effects of a stressor and subsequent stress exposure.

When I look at this, I acknowledge the fact research is still continuing but through experience I couldn’t help but think the relationship between stress and the developing brain seems like a well-known secret.

Resilience

“In some circumstances, exposure to stress may be followed by an increased resistance to later stress (a steeling effect), rather than a sensitization or increased vulnerability.” (Rutter, 2012)

Hard life now, easy life later - a saying or a truth behind it?

We have a disposition to believe that if we do the hard work now, the results will come faster.

While in some cases this may be true, the results certainly don’t come immediately and that leads to people diverging and taking the path of least resistance.

When reading up on different views of what it means to make hard choices, I came across the point that making hard choices will lead to a meaningful life, not necessarily an easy one.

It really resonated with me, as living a life with purpose has simplified mine in many ways.

Whether it’s the clarity we have on the world around us, the understanding we have of ourselves, or just the situations we encounter, this will ultimately lead to less regrets as you wouldn’t have to go back and forth on your morals.

Less regrets → less stress.

The ability to remain in the present is a skill in itself and can enable us to lead a better life.

By taking difficult choices now, I find fulfilment in acknowledging my efforts to progress and develop while simultaneously avoiding regrets.

In some cases, these regrets are ones that follow us like an anchor, getting heavier with every step we take.

It may seem obvious, but continually beating yourself up about the past or just being stuck in it can be at the detriment of our health.

Rumination refers to a repetitive and passive focus on negative thoughts, emotions, or past events, which can perpetuate a cycle of being stressed.

This is because, these thoughts, emotions, or past events are relieved as stressors as if they are happening in real time, which causes the body to react as if it is being stressed in the moment.

Essentially, you keep your stress response hyperactive leading to that dysregulation of cortisol, us feeling even worse, and perpetuating the cycle of being ‘stressed out’.

So where does resilience come in?

If I were to ask what resilience means, most would use the phrase ‘bounce back’ to describe recovering from some sort of adversity.

Objectively, we can identify a resilient person through their experiences and the way they handled them, but what about when the adversity starts from within?

What would you do?

As a technique I use quite often, whether it’s a reminder of why I opt for the more taxing route or when I have come face-to-face with adversity, one point I will continue to bang on about is framing.

Are my emotions based on all-or-nothing thinking? What are compromises that can be made?

Going from “Why me?” to “What can I learn from this and what development points has this afforded me?”

Instead of venting over not completing my to-do list, reprioritising and stepping back to see why my expectations didn’t match up with my action. Sometimes it is as innocent as me just wanting to get something done earlier than necessary.

If the negative thoughts still linger, other ways of breaking the cycle of rumination is talking to friends or family who can provide the perspective and support you need.

Whatever the situation is, you don’t want to be in a position where resilience and grit is the catalyst for every action.

That would only lead to a miserable life… and more stress.

Trauma and Resilience

When looking into the causes of stress it became apparent that there was some sort of fixation with linking stress and trauma, and I found myself asking this question:

Is trauma a necessary element in building resilience?

For example, when reading the review article ‘Coping with Stress During Aging: The Importance of a Resilient Brain’, they stated the following:

“the cause of affective disorders is not the traumatic event itself, rather than the way in which these events are processed psychologically by each individual. This ability to successfully cope with and overcome the aftermath of a trauma is known as resilience.”

A common notion is that trauma has a net-positive impact on resilience-building and mental toughness.

Research by Seery et al. (2010) supports the notion that exposure to moderate levels of adversity can lead to better psychological wellbeing compared to exposure to a high level of adversity or none.

Conversely, Masten, 2001 highlighted that studies have found factors such as parenting to predict child competence, which also alludes to the interplay between genetics and our environment.

An article by the Science of Bio Genetics presents a balanced view on this:

“Childhood trauma can have a profound and long-lasting impact on an individual’s stress levels. Studies have shown that individuals who experienced traumatic events during childhood are more likely to have elevated stress levels throughout their lives. This can be attributed in part to genetic factors.”

The cultivation of resilience is multifaceted and trauma has the ability to toughen or sensitise depending on the person.

Once again, as with the relationship we have with stress, balance is key and it has been reaffirmed that there is neither a sole nor ideal path to forging our psychological strength.

What can we take away from all of this?

Although a challenge I was willing to take on, ironically this was one of the most stressful posts to write.

Knowing when to stop digging for answers, meeting roadblocks on research developments without any conclusive answer, and the managing the remoteness of the research when trying to relate it to our daily lives.

When returning to Lupien’s 2009 paper I cited earlier, I found it interesting how the researchers raised a point of contention in the scientific method behind investigating our relationship with stress, yet researchers today still acknowledge their results to be indicative of humans:

“Studies of stress in adolescent rats cannot be translated directly to humans because the brain areas that are undergoing development during adolescence differ between rats and humans.”

Time and time again, rats where used as reference points to present areas for further exploration which got frustrating at some points.

A point that this reiterated for me was the fact that stress is a personal experience.

I reflected on my relationship with stress throughout writing this post. At most my awareness of what it is has grown, but my attitude towards stress hasn’t changed.

A lot of the time, I find that I am my biggest source of stress.

My standards, expectations, ambitions - yet I still thrive on it.

I’ve been on either side: when chronic stress has led to being burnt out from the illusion of raising my baseline efforts, to moments of acute stress which have led to eye-opening experiences where I have dispelled my self-doubt.

In the short-term, you may revel in stressful situations, but in understanding myself better over the past few years, I know sustainable growth is key.

Sometimes we can very much get into our own head, stopping us from seeing the bigger picture, and following on from ‘The Spotlight Effect’, it would be a fitting narrative to end on the fact that we have the tendency to get into our own head, but this post is much deeper than that.

‘If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change’ alludes to my point of framing as a way of handling stressful situations. Simultaneously, it can only get you so far.

In part, you can minimise the effects of chronic stressors by not letting the acute stressors get to you, but the bigger picture is the way you treat yourself today, mentally and physically.

Remember that stress is a response.

To say that you thrive on stress or pressure catches up to you.

We like to overcomplicate the simple things:

Practising sleep hygiene

Incorporating exercise into your routine

Practising mindfulness; whether its spirituality, breathwork, meditation, etc.

A classic: have a balanced diet - it doesn’t have to be extreme

Boring, but reliable.

We desire a way to eliminate the trade-offs and challenge ourselves to no avail as a way to disprove the logic we have at present time.

These points of reflection do not only counteract the environmental causes of stress, but also our genetic predispositions which are key to understand in order to manage our stress effectively.

They are simple reminders, but also a reminder that we tend to add elements rather than strip some away when we seek solutions.

I found this post intriguing to write and I learnt a lot of lessons about what is happening internally, the landscape of research, and the role of our upbringing.

As a topic, there is much more to explore but there is only so much I can fit into one post.

If you enjoyed this post and want to see more, I’ll be more than happy to hear from you.

If you found this post helpful, hit subscribe and get unique and actionable insights into self-improvement every fortnight.

P.S.

How has your perception of stress changed?

Such a rich reflection, stress really does shift with each life stage. Your insights highlight how personal and layered our relationship with it can be!

Great article. Thanks for sharing!